- Partner Grow

- Posts

- Capital One Snaps Up Brex for $5.15B

Capital One Snaps Up Brex for $5.15B

Capital One - Brex acquisition deep dive

👋 Hi, it’s Rohit Malhotra and welcome to the FREE edition of Partner Growth Newsletter, my weekly newsletter doing deep dives into the fastest-growing startups and S1 briefs. Subscribe to join readers who get Partner Growth delivered to their inbox every Wednesday morning.

Latest posts

If you’re new, not yet a subscriber, or just plain missed it, here are some of our recent editions.

Partners

Introducing the first AI-native CRM

Connect your email, and you’ll instantly get a CRM with enriched customer insights and a platform that grows with your business.

With AI at the core, Attio lets you:

Prospect and route leads with research agents

Get real-time insights during customer calls

Build powerful automations for your complex workflows

Join industry leaders like Granola, Taskrabbit, Flatfile and more.

Interested in sponsoring these emails? See our partnership options here.

Subscribe to the Life Self Mastery podcast, which guides you on getting funding and allowing your business to grow rocketship.

Previous guests include Guy Kawasaki, Brad Feld, James Clear, Nick Huber, Shu Nyatta and 350+ incredible guests.

Brex acquisition

Introduction

The Brex-Capital One deal isn't your typical down-round disappointment—it's a perfect split-screen of venture returns. Capital One paid $5.15 billion for what was once a $12.3 billion unicorn. Early investors are celebrating. Late-stage backers are calculating losses. Same company, radically different outcomes.

On the surface: a fintech darling getting acquired at a steep discount while its chief rival, Ramp, hits $32 billion and $1 billion in ARR. But look closer, and it gets more interesting.

Brex didn't lose by building inferior tech or missing product-market fit. It lost by mistiming its pivot. The move that likely saved the company—abandoning SMBs for enterprise clients in 2022—also generated massive backlash and momentum loss precisely when Ramp was accelerating.

The founders—Pedro Franceschi and Henrique Dubugras—had sold a payments company in Brazil for over $1 billion before turning 17. They knew how to build. They'd lived inside fintech infrastructure. Franceschi shipped credit products across global markets. Dubugras understood scale.

They'd both seen the same problem: startups underserved by legacy banks, corporate cards that treated founders like credit risks, and expense management built for enterprises, not growth companies.

And here's the brutal efficiency: Ribbit Capital's Series A turned into a 700x return. Four years from $7 million check to billion-dollar exit. Not because Brex raised the most or grew the fastest. Because they built something valuable enough that a bank moved before the market corrected further.

History

Brex didn't start as the $12 billion fintech darling that Capital One just acquired. It started as something far less certain: a pivot by two teenage founders who'd already sold a company for over a billion dollars.

The company was originally supposed to be a VR headset startup when Pedro Franceschi and Henrique Dubugras applied to Y Combinator's winter 2017 batch. But these weren't typical 19-year-old founders fumbling through first ventures. They'd already lived inside high-stakes payments infrastructure.

At 16, they'd built and sold a Brazilian payments processor that raised $30 million and eventually got acquired for more than $1 billion by a strategic investor. They understood merchant acquiring, fraud detection, and how money actually moves between businesses.

They'd both seen the same problem: startups drowning in outdated corporate card applications, and most traditional banks optimizing for "established businesses" instead of "what actually powers growth companies."

So they built for the people legacy banks ignored. First came the corporate card: underwriting based on cash balance and runway, not personal credit scores or three years of tax returns. Instant approvals. Higher limits. Rewards that actually mattered to startups—points on software spend, not airline miles.

Then the spend management platform: expense tracking, bill pay, and banking infrastructure specifically for companies that were burning capital to grow. Not "here's a credit card," but "here's how you manage every dollar leaving your company."

The company raised over $1.5 billion across multiple rounds. Ribbit Capital led the $7 million Series A. DST Global, Kleiner Perkins, Y Combinator, Peter Thiel, and Max Levchin all backed them early. By 2022, the valuation hit $12.3 billion.

The thesis stayed constant: financial infrastructure should help companies grow faster, not gatekeep based on legacy banking requirements.

Then the pivot. In 2022, Brex abandoned tens of thousands of SMB customers to focus exclusively on enterprise clients and software. Four months later, the market turned. Two years after that, Capital One moved.

Deal breakdown

Here's what makes the numbers brutal: $5.15 billion for a company valued at $12.3 billion just three years earlier. A 58% haircut for a fintech that once competed directly with banks. Closed before regulatory uncertainty could kill momentum.

The timeline tells the story.

January 2022: Brex hits $12.3 billion valuation in Series D-2. Mid-2022: Company abandons SMB customers to focus on enterprise. August 2024: Secures EU banking license. January 2025: Capital One announces acquisition. Done before Q2 ends.

But here's what Capital One actually bought.

The product: A spend management platform with corporate cards, bill pay, and banking infrastructure. Strong tech, loyal enterprise customers, zero consumer moat. Ramp built the same thing faster and raised at $32 billion.

The clients: TikTok, Robinhood, Intel, and a roster of high-growth companies. Plus immediate EU market access through Brex's freshly minted banking license—no regulatory delays, no integration headaches.

The real asset: $13 billion in deposits sitting at partner banks and money-market funds. After swallowing Discover Financial for $35 billion five months earlier, Capital One needed deposit growth and corporate banking distribution. Brex delivered both instantly.

What stays behind: The Brex brand initially. Franceschi remains CEO post-acquisition. A "standalone operation" that Capital One will "integrate over time"—corporate speak for gradual absorption into Capital One Business.

The deeper signal: Brex chose liquidity over growth. If the fintech disruption thesis were real, why sell at half your peak valuation? The founders saw the ceiling—enterprise spend management is table stakes, not transformative. Capital One didn't care.

This follows the pattern. Marcus worked because Goldman kept it separate. Venmo worked because PayPal left it alone. Everything legacy banks built internally—mobile-first products, API platforms—launched late and struggled.

Brex proves demand exists for modern corporate cards. But Capital One paid down-round prices for distribution and deposits, not defensible technology.

Brex value proposition

To understand why Capital One paid $5.15 billion, you need to understand what Brex actually solved. Not another corporate card. Not incremental fintech improvements. A fundamentally different approach to the problem that matters most in startup banking: the gap between needing capital and accessing it.

The spend management architecture did one thing obsessively well—eliminate the friction between growth and financial operations. While traditional banks excelled at serving established businesses with predictable revenue, Brex was designed specifically for companies burning capital to scale: the high-velocity environments that determine whether fintech feels like infrastructure or an obstacle.

Here's the product advantage: banks are gatekeepers. They underwrite on history, require personal guarantees, optimize for risk avoidance—everything backward-looking. Brex is an enabler. Forward-looking underwriting, instant approvals, built exclusively for companies where cash balance and runway matter more than three years of tax returns. No credit checks on founders, no collateral requirements, no waiting. Just working capital for the exact customer segment legacy banks ignored.

The real-world difference wasn't subtle. Brex delivered corporate cards within minutes, expense management without implementation cycles, bill pay without wire transfer fees—not banking products requiring CFO oversight. For startups where speed defines survival—product launches, hiring sprints, market expansion—Brex became the default infrastructure.

And this mattered more as venture capital shifted from abundance to scarcity. Fundraising happens quarterly. Operating expenses happen daily, compounding into burn rate pressure. Brex owned the layer where startups actually manage cash.

The customer momentum validated the approach. From launch to enterprise clients like TikTok, Robinhood, and Intel—companies that could afford any banking partner but chose Brex. Not because of aggressive sales or legacy relationships. Because when you give finance teams infrastructure that moves at startup speed, they migrate immediately. Speed is a feature CFOs notice on day one.

Capital One saw all of this. The product differentiation, the enterprise traction, the market positioning in their weakest area—corporate banking for growth companies. Brex wasn't building toward profitability. They were building toward acquisition.

Why Capital One bought Brex

Capital One isn't buying a fintech wrapper. They're buying the distribution layer before another bank owns corporate spend management.

$13 billion in deposits. That's not just customer traction—it's balance sheet fuel. Every dollar Brex manages validates that startups and enterprises will trust non-traditional banks with treasury operations. Capital One just bought that validation before JPMorgan or Goldman could build competitive products.

Then the execution advantage. Brex spent years since its 2017 launch solving the "corporate banking for growth companies" problem at the product level. Capital One just bought all that iteration, all the failed underwriting experiments, all the architectural insights that made instant approvals work without blowing up credit losses. They didn't compress their development timeline—they eliminated it.

But here's the deeper play: Capital One is hedging against irrelevance in business banking. Right now, they're a consumer credit card company with decent commercial products. But the industry is shifting toward embedded finance that executes treasury workflows autonomously. Platforms where "modern banking" means "zero friction," not "better mobile app."

Brex represented the interface that wins in that future. Capital One couldn't let enterprises discover that corporate banking works better at software speed, not bank speed. So they bought the threat before it matured into a challenger bank.

The customer base matters more than the technology. Capital One already has banking infrastructure—regulatory licenses, deposit insurance, balance sheet capacity. What they didn't have was credibility with high-growth companies. Brex gave them that. And immediate access to clients like TikTok, Robinhood, and Intel, which their commercial teams couldn't win organically.

The EU banking license sweetens everything. Capital One just paid $5.15 billion to instantly operate corporate banking across 30 countries without years of regulatory approvals. Brex spent months navigating EU licensing. Capital One inherited the access on day one.

The timing couldn't be better. Fintech valuations cratered. Brex needed liquidity. A $5.15 billion check solves both problems while Ramp is still private and overvalued at $32 billion.

What it means for founders

The Brex acquisition exposes a brutal truth about fintech startups: the enterprise pivot is a viable exit, not a viable moat.

Most founders are fighting over features - better rewards, faster approvals, slicker mobile apps. It's the most obvious place to compete, which makes it the most expensive. You're racing against Ramp's next funding round, fighting on growth metrics against well-capitalized competitors, and praying your product stays differentiated for twelve months.

Brex went one level higher: the enterprise layer. Spend management, treasury workflows, and EU banking licenses on top of infrastructure they didn't build. They didn't create better payments rails. They packaged existing card networks and banking partners into a product that felt like modern infrastructure, not legacy banking.

That positioning made them acquirable, not defensible. Capital One couldn't see Brex as a long-term threat because Brex depended on banking infrastructure Capital One already owned. They sat above the hard regulatory work, capturing customers without controlling distribution. That's why the exit happened at half the peak valuation—before competitors made corporate cards commoditized.

Now Pedro Franceschi stays as CEO, reporting into Capital One's commercial banking division. The same division that just absorbed Discover Financial in a $35 billion deal. Franceschi built a company that shipped fast by staying independent and founder-led. He's walking into a structure where integration timelines matter more than product velocity.

The $5.15 billion exit sounds like validation. It's actually a warning. Brex sold because they saw the ceiling coming. Ramp hits $1 billion ARR, Mercury hits $650 million ARR, every bank launches instant corporate cards - and suddenly your "modern spend management" is table stakes inside every commercial banking product.

If you're building fintech, ask yourself: are you capturing value in a layer you control, or repackaging legacy infrastructure with better UX?

Franceschi cashed out at the right time. The question is whether he can still build inside a bank - or just sold into corporate integration hell.

Closing thoughts

The Brex story isn't about disruption. It's about recognizing when growth caps—and exiting before the market reprices you further.

Three years from $12.3 billion valuation to $5.15 billion acquisition. Not because they built inferior technology, hired weaker talent, or lost product-market fit. Because they packaged existing banking infrastructure into a product that felt modern—and sold before corporate spend management became commoditized.

Everyone's obsessed with building moats. Brex built distribution. They connected card networks and partner banks to customers who wanted banking that moves fast, not banking that gatekeeps. That positioning made them valuable to exactly one buyer: whoever needed enterprise deposits and EU market access without building from scratch.

Capital One wrote the check.

Here's what founders should take from this: liquidity beats valuation. The fintech layer isn't defensible long-term, but it is acquirable—if you exit before competitors saturate the market. Brex saw Ramp hit $32 billion, Mercury scaling fast, every bank launching instant cards. They knew the window was closing.

Ribbit Capital turned $7 million into a 700x return. Later investors took haircuts but got liquid.

That's not failure. That's what happens when you build something valuable enough to acquire, competitive enough to compress, and exit before the math gets worse.

The best exits aren't about peak valuation. They're about actual liquidity.

Here is my interview with Sergiy Korolov is the Co-CEO of Railsware and co-founder of multiple products

In this conversation, Sergiy and I discuss:

-What’s the differentiation strategy against SendGrid and Mailgun

-How is Railsware actually using AI internally today?

-What’s the current split between self-serve PLG motion and any sales-assisted deals?

If you enjoyed our analysis, we’d very much appreciate you sharing with a friend.

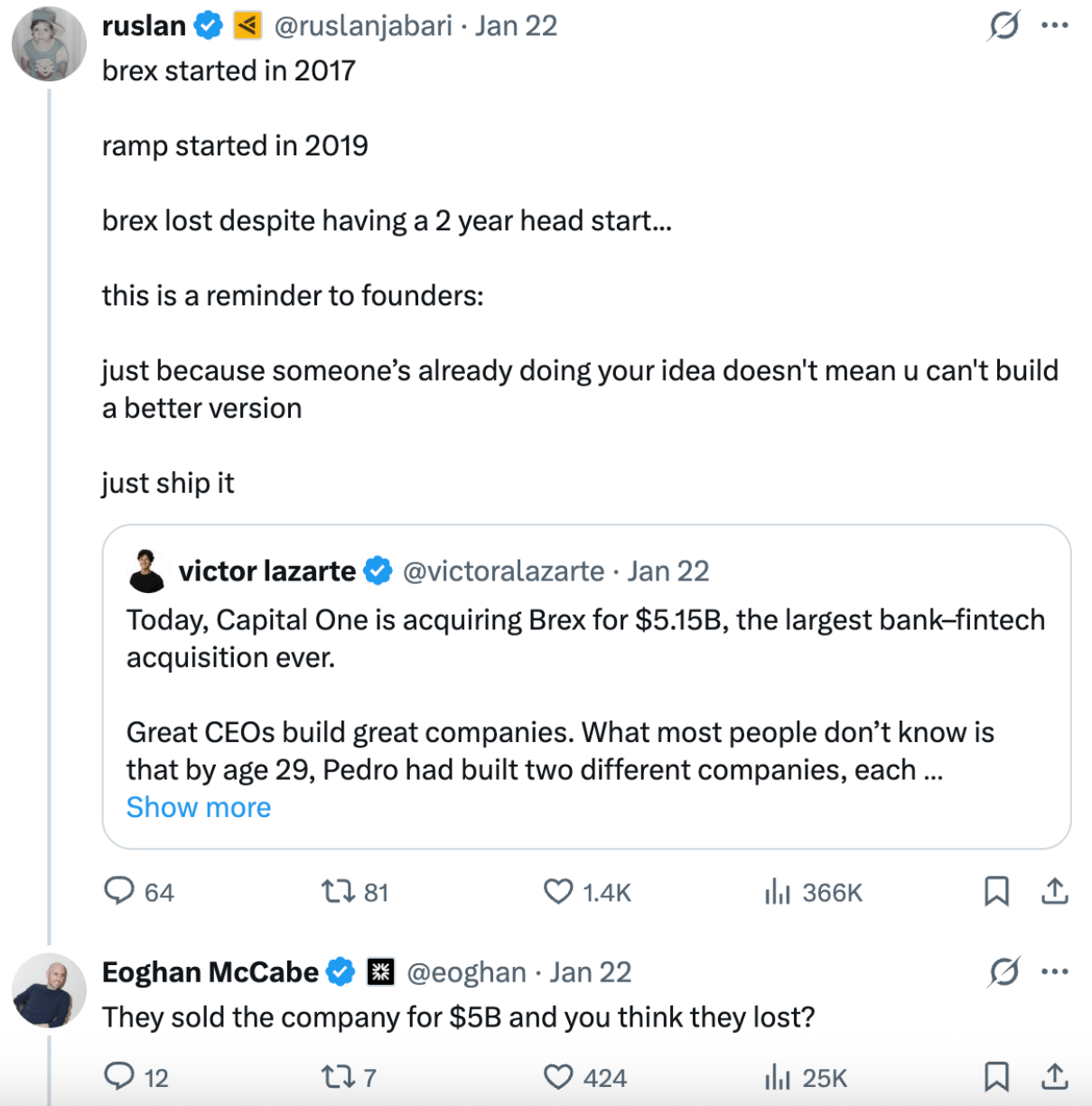

Tweets of the week

Here are the options I have for us to work together. If any of them are interesting to you - hit me up!

Sponsor this newsletter: Reach thousands of tech leaders

Upgrade your subscription: Read subscriber-only posts and get access to our community

Buy my NEW book: Buy my book on How to value a company

And that’s it from me. See you next week.

Reply